If someone were to give you a $5,000 raise tomorrow, how would this change your behavior? Economists have a few basic theories for the effects of income changes upon work/leisure consumption, which can be used to predict the effects of tax or welfare policies, among other things. Some people clearly fall under the umbrella of one theory, but many more lie in a gray area of reaction. Here’s a quick quiz to see:

You work at a job paying $15 an hour. Tomorrow, your boss tells you he will be paying you $20 an hour thanks to your superior skills. What do you do?¹

a) Work less hours, because I’ll have more/the same amount of money. It’s Netflix time.

b) Work more hours, because suddenly the “cost” of lying around for an hour just went up—I could have made $20!

c) I think I’ll buy an Xbox/new purse.

If you answered A: It looks like you are experiencing the income effect! Leisure is a normal good—that means that when your income goes up, you demand more of it, and when your income goes down, you demand less of it! Because your income just went up, you will demand more leisure. Enjoy your movie watching!

If you answered B: It looks like you are experiencing the substitution effect! There is a “cost” to leisure—opportunity cost. For each hour you spend lying around you could have been earning money. As your wage increased the relative cost of leisure increased—you are now giving up $20 for each hour you spend doing nothing. When the price of a normal good (see above) increases, the demand decreases, so you will consume less leisure, and work more hours.

If you answered C: You should really evaluate your consumption patterns. Invest yo' earnings!

“But wait,” you say, “those effects are working opposite of each other!”. Right you are, my friend. The beauty of economic theories is that sometimes they completely contradict each other, which accounts for all the people who think very differently than you do! A lot of times, these effects work opposite each other to create an overall neutral effect to income changes. How strong each effect is for a given person depends entirely on their preferences, which can be drawn out graphically as “indifference curves” (more on this later). Here’s another quiz to explain this further:

1) Fred works at an ice cream shop, and hates his job. He has to listen to crying children all day, but the job pays him just enough to get by, so it’s worth it. He gets a 50% raise. Does the income or substitution effect apply to him?

a) income effect (wants more leisure)

b) substitution effect (works more hours)

2) Angela works at a tech company that sounds like “frugal”, and it’s her dream job—work is her life! She gets a promotion & raise. What does she do?

a) Stay 2 extra hours a day—now she has even higher expectations to fill.

b) Start going home at 5.

Correct Answers:

1) A

2) A

Now do you see how an individual's preferences might affect which effect applies to them? This is extremely important to consider when implementing any policy changes, particularly income transfers (taxes or welfare, etc.). Oftentimes we have the best intentions, but don’t consider that others may not feel the same way about working or leisure that we do. The substitution and income effect are particularly interesting when it comes to unemployment insurance and the earned income tax credit (EITC), though this is a conversation for another time.

In their most basic form, the income and substation effects describe the reactions actors have to price changes. As the price of an item changes, so does its relative price (what you give up to get it)—which is the substitution effect. As the price increases or decreases, this also either constrains or creates new income, which is the income effect.

The Gist:

The income effect refers to the reaction in demand for goods due to income changes, and the substitution effect refers to the reaction in demand for goods due to changes in the relative prices of the goods.

¹Let’s assume that our quiz characters have no debt, kids, and other annoying things like that. Classic economics, oversimplifying like crazy!

Popular mobile payments app Venmo enjoys the benefits of behavioral economics biases, causing users to feel less pain from spending money. Learn how it works, and how businesses can capture the "Venmo effect".

Deep-dive into the increasingly personal way we interact with brands, fueled by Snapchat and Instagram.

Some musings on the benefits of the changing cultural consumption landscape (including the shift to streaming of music and TV).

Females are prescribed psychiatric drugs at much higher rates than men. Females also tend to be more emotional (wide generalization). Processing emotions takes time, and time spent on emotional work is time NOT spent generating revenue. Ultimately, the trend of medicating female emotion (and emotion in general) is a money-driven one.

The Internet of Things (IoT) is the future of technology, but also represents some interesting economic phenomena not-so-frequently seen.

We all hate surge pricing, but it's a great way for Uber and its drivers to capture more value. What if GrubHub, Starbucks, etc. charged customers more during peak hours in order to pay service workers better? Could we ever break the cycle of reliance on cheap labor?

Price discrimination is a way that companies can make more money by understanding how much different consumers will pay for the same good. Here's how it works.

What's the economic explanation behind the rise of the term "basic"? Is this a new phenomenon, or merely a quality of human nature evident due to economic and technical changes?

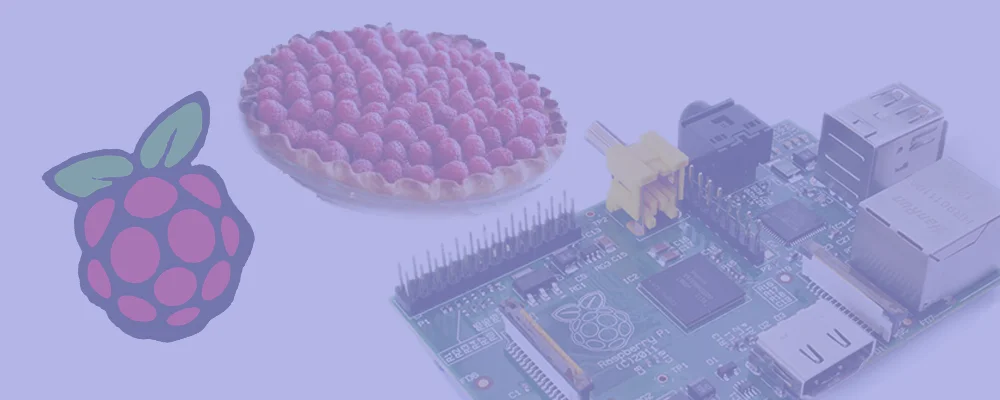

Would you pay $35 for a Raspberry Pi? No, not the food, it's a miniature computer! This device can be revolutionary for the 75 million Americans without internet access.

Do you ever forget the difference between nominal and real? Do you wonder why financiers analyze Yellen's words like a text from a crush? If so, this is the article for you!

When fruit flies, it fails. Industrial agricultural practices have brought us berries in January, but at the cost of quality. Read about why harvesting heirloom varieties is important for taste, small farmers, and the environment.

It used to be that the strongest hunter had the most value in society. Today, the nerdy ideas man has the most worth. What happened?

Innovation is cyclical and inspired by other innovation. For example, this article was inspired by my purchase of innovative new ice cube trays. Read about how product variety is created, and how it can be a bad thing.

You may hear the terms horizontal and vertical integration tossed around in business (Businesspeople love fancy strategy terms). Learn how Standard Oil used integration to become a monopoly and how one might benefit from integration today.

Will a big engagement ring buy you happiness? What about donating blood? How do you properly motivate someone? If you are looking for a job, is city size a factor? Why are smartphones important for the poor to have? All this and more.

America is in trouble if the cost of Third World labor increases. As has been the tradition for all of human history, our economic success depends on the accessibility cheap and near-slave labor. How can we grow when this ends?

Some would claim that it is human nature to capitalize upon opportunities. Arbitrage was born of this human urge to take advantage of money-making opportunities.

Efficient appliances seem like a great way to reduce our energy use, right? Wrong - in the long run, they end up causing massive increases in energy use due to cost reductions.

"Run out of oil? Never!"

In all likelihood, this won't transpire, but if you aren't familiar with the idea of peak oil (or like to deny it), answer all your questions here.

Most people could tell you that oil and energy is critical to our economy and planet. In fact, energy is the foundation of all growth, but it isn't included in our economic models. Here's why the discipline of economics needs to be re-organized.

This edition of Deciphering Data brings you the answers to all these pressing questions and more:

- At what time of year do most break-ups happen?

- Why are tiger-moms a thing in the US and China?

- How do different people around the world think success happens?

The rise of American affluence gave us the luxury of choice and ability to be picky about what we like. Combined with newly formed marketing and advertising industries, consumer preferences developed that made perfect substitutes an economic unicorn. (If you don't know what a perfect substitute is, no worries, read on!)

Indifference curves are not graphs of who cares less, rather, they show different combinations of goods that can give a person a certain level of utility, or well-being.

Do middleman apps make our lives better? What about the lives of their employees? Do Uber-like services improve consumer welfare? How do recessions affect birth rates? Why does the US have relatively high infant mortality?

Find the answers to all these questions and more.

Does this man look like he is substituting or complementing these apples? Trick question: apples are inanimate, and can't be complimented.

The best data visualizations from around the web. Learn about online dating, music tastes, political preferences, violence, and earthquakes.

Did you know that higher gas prices might be better for us all? Industrialism is great, but creates negative externalities, such as pollution. Pigovian taxes reduce negative externalities and aim to also reduce distortionary taxes, like income tax. Win-win!

Don't be like this guy and let your money sit in the bank. Start investing with some simple tips!

Money represents a social agreement, which has implications for how we value wealthy people. Bitcoin replaces the need for this social agreement with technology, and in doing so challenges the values we ascribe to wealth.